However, we need more imagination to grasp how different the lives and preoccupations of the members of The Outdoor Art Club were during those years. Before Influenza became a pandemic in 1918, the women of the OAC were already mobilized as American boys had been sent to the European war front in 1917 to fight what was then called “The Great War.”

Founder Agnes Cappelmann was President and wrote at the time, “This terrible, chaotic state through which we are passing today makes women want to play a part in that which is ‘self-sacrifice’. How they can best serve their fellow man is through the medium of the Red Cross and War Relief work.”

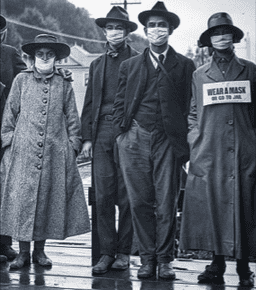

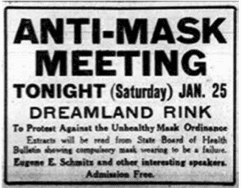

This Anti-Mask League ad appeared in January 1919 in the SF Chronicle. Mill Valley ordinance #202 required wearing masks to avoid fines ( $5 to $100) or jail (up to 90 days).

This Anti-Mask League ad appeared in January 1919 in the SF Chronicle. Mill Valley ordinance #202 required wearing masks to avoid fines ( $5 to $100) or jail (up to 90 days).

Dozens of layettes were made for expectant Belgian mothers … tobacco was sent to the base hospitals in France,” etc. Locally the Club adopted the YMCA at Fort Baker, and the ladies’ embrace of those soldier boys was complete. They curtained the building’s windows and added “many other homelike touches.” The ladies entertained the boys, once with a Vaudeville performance, and also at a Christmas party with “fifty home-made cakes. … The men from the forts have also been our guests at the two dances given during the year.”

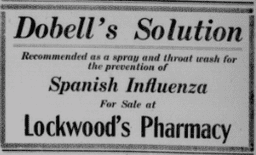

In 1918, the Mill Valley Record informed town citizens about both the war and the flu with lengthy columns. Descending headlines in the October 19, 1918 edition urged readers to commit to reading the entire column: “UNCLE SAM’S ADVICE ON FLU — U.S. Public Health Service Issues Official Health Bulletin on Influenza — LATEST WORD ON SUBJECT — Epidemic Probably Not Spanish in Origin—Germ Still Unknown—People Should Guard Against ‘Droplet Infection’—Surgeon General Blue Makes Authoritative Statement.”

In their War Service Section, the OAC ladies saw themselves as guided by the Red Cross, then a highly esteemed organization. Every M.V. Record edition contained news and views.

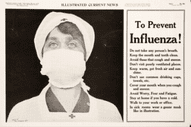

An image of a Red Cross nurse published in Illustrated Current News, 1918.

An image of a Red Cross nurse published in Illustrated Current News, 1918.

In the U.S. the influenza began at an army training camp in Kansas. The majority of those killed by the 1918 flu were in the prime of life, often in their 20s, 30s and 40s, rather than older people weakened by other medical conditions.

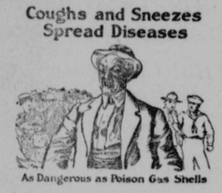

The reality of U.S. doughboys having to face poison gas was was food aid. never far from the thoughts of those at home.

The reality of U.S. doughboys having to face poison gas was was food aid. never far from the thoughts of those at home.

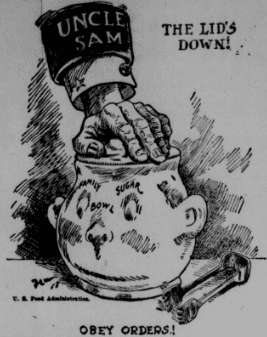

In August of 1917, Congress created a Food Administration whose purpose was to educate Americans and “to provide further for the national security and defense by encouraging the production, conserving the supply and controlling the distribution of food products.” Headed by future President Herbert Hoover, this volunteer body consisted primarily of women, charged with helping to feed the Allied Forces.

Consumption of sugar was not only frowned upon, it was rationed.

Consumption of sugar was not only frowned upon, it was rationed.

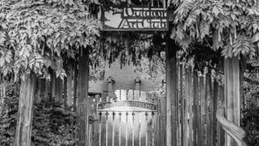

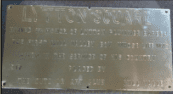

Despite the community’s worries about the war and their curtailing of food consumption, it was the Influenza epidemic that brought grief to the town. The first Mill Valley boy to die in the war was the son of OAC member Beulah Barber. Her boy, 18 year-old Lytton, did not die on a European battlefront, but died at a stateside army training camp, “… ere his overseas orders had come.” The whole town mourned and later chose to honor him by naming the village center, Lytton Square. At the 1918 Memorial Day festivities “One of the beautiful wreaths of roses which adorned the tables at the Outdoor Art Club breakfast given Thursday was placed over the tablet at the base of the Lytton Square flagstaff.”

Lytton Square – named in honor of Lytton Plummer Barber, the 1st Mill Valley boy whose life was given in the service of his country.

Lytton Square – named in honor of Lytton Plummer Barber, the 1st Mill Valley boy whose life was given in the service of his country.

That heartfelt affection was most poignantly expressed by Founder Carrie Klyce in her history of the OAC written in 1940: “With the passing of Mrs. John Finn, our beloved friend and founder, the flag in Lytton Square stood at half mast October 26, 1918. Her memory will be cherished by unnumbered people who were recipients of her loving courtesies. … Mrs. Finn once said that she thought it right during the First Great War time for our Club to be the sheltered cove of refuge in which to meet so as to forget the terrible happenings of the outside world; just to have friendly gatherings, thoughts of gladness and rest for that hour, that we would be stronger workers at home or elsewhere

from that sheltered hour of relaxation.”